Babul Asan Udh Jaana

[Oh Father, I’m Going to Fly the Nest]

By Sikh Family Center

Manjeet Kaur married Aman Singh in Punjab, and joined him a year later in the United States once her immigration cleared. All her cousins envied her because she was going to live in the United States! So, Manjeet hid her discomfort about how Aman had hardly spoken to her since they got married.

Aman’s mother traveled to Punjab to accompany Manjeet on the journey to her new home. Aman’s family had demanded dowry both before the wedding, and again once Manjeet’s paperwork had cleared. Manjeet’s family, not wanting this to stand in the way of their daughter being with her husband, fulfilled their demands before bidding her farewell.

Shortly after Manjeet arrived in the United States, her younger sister Simrat sensed something was wrong. Manjeet was not calling home even weekly, nor responding much to WhatsApp messages. Nor was she answering Simrat’s calls. Perhaps Manjeet was busy settling into her new promising life, Simrat thought. But when Manjeet would call home, she was quiet on the phone, responding with brief “yes” or “nah” answers. There was no sign of the excitement Simrat expected.

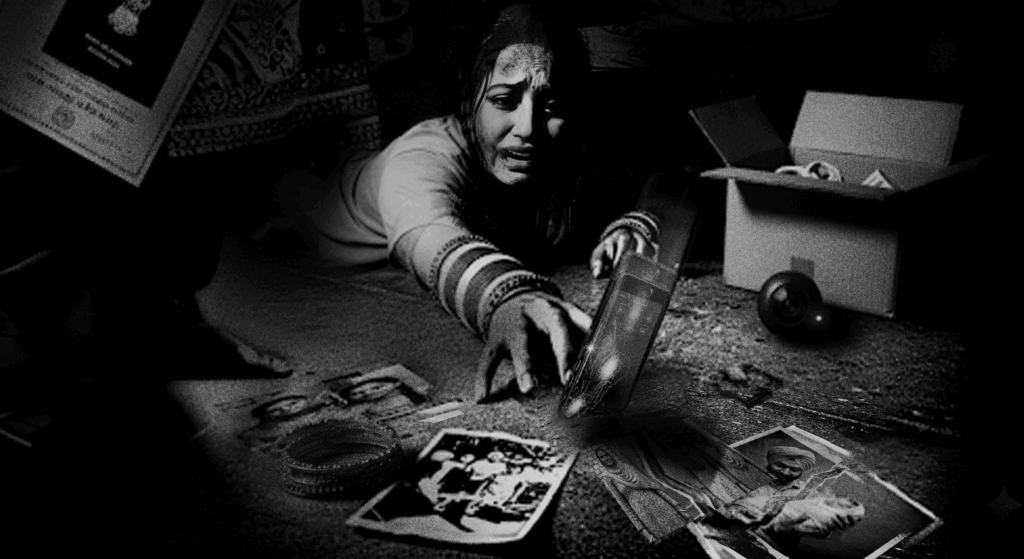

She confided that her in-laws had confiscated her official documents, including college and professional certificates, in an effort to cut her off from her identity and independence. Her in-laws deleted all her family pictures first, then destroyed her phone. She had an older phone which she was using to call her family via WhatsApp, but it did not have a SIM card or data.

Manjeet did not know the neighborhood and no one there would know she was living in this house with her in-laws. She was forbidden from opening the door and stepping out. Occasionally, her in-laws took her to Gurdwara, where they were very active arranging paaths for their family and participating. When they took her, they made sure they never left her side, making it impossible for her to reach out to anyone in the sangat and confide her plight.

Her mother-in-law barred her from leaving the house without her. Or even spending time alone with Aman.

“My son will never be yours, he is my son,” Aman’s mother had declared.

When Manjeet expressed a desire to go out or get a job, Aman would become violent. He would push her into the wall, drag her down the stairs by her hair, squeeze her face, and at times her neck.

As per the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention, pressure around the neck can result in a loss of consciousness. Death can occur in just over 1 minute to just over 2 ½ minutes.

Survivors of strangulation are at a higher risk of being re-assaulted, and…750% more likely to be killed by the person causing abuse.

At night, following such episodes, Aman would remove his pagri, slap himself, pull his own hair, and even hit his head against the wall. This was his way of apologizing for the harm he had caused. When Manjeet said she thought they should separate since they were both unhappy, Aman threatened to kill himself.

Manjeet’s in-laws allowed her to call home as long as they could listen in on her conversations; they asked her to place her calls on speaker phone saying, “What do you have to hide?”

Manjeet’s parents urged the in-laws to let Manjeet find a job, pursue her career, hoping this would give her some independence. They told the in-laws that this way she would also be contributing to the household expenses. Her in-laws refused.

When Manjeet sounded really low and disclosed more about the abuse she was experiencing, her parents finally threatened to involve the police. This prompted the in-laws to promise they will keep Manjeet happy.

They took her for a drive around the neighborhood after the conversation. Once.

Simrat, now very worried, contacted a distant relative that lived near her sister Manjeet, to see if they could intervene. These relatives called 911 and requested the police to conduct a wellness check. When the in-laws saw the police outside, they quickly coaxed Manjeet into not saying anything. They also promised things will change for the better.

Manjeet, wanting to give her Anand Karaj another chance, answered the door, said she was fine, and assured them there was nothing to worry about. The police left.

Then, Manjeet’s in-laws blamed her for the police’s visit. Everyone stopped talking to Manjeet, except to threaten her or curse at her.

Meanwhile, when Simrat tried to talk to their relatives in the area again, the relatives expressed anger and said they did not want to be involved as Manjeet had already turned the police away once before. They said their time had been “wasted.”

Then all WhatsApp calls from Manjeet stopped, entirely.

Simrat contemplated traveling to the United States to find her sister. But, she didn’t even know the exact street address, just had the name of a city! And she was worried that she may not get there in time.

Concerned about Manjeet’s safety, Simrat searched online for resources in the U.S. and reached out via Sikh Family Center’s Helpline.

Sikh Family Center’s peer counselor listened carefully to Simrat and all her concerns before asking her for any necessary information. Simrat said she was relieved the peer counselor had seen situations like this before, because she felt totally lost. She shared her family felt so stupid for sending their daughter into death’s mouth. The peer counselor assured her that her gut instinct mattered, and they could work together and build an urgent safety plan.

The peer counselor discussed strategies with Simrat to help keep Manjeet safe, to minimize any self-harm, including:

By asking her very direct questions about suicide.

As per the National Institute on Mental Health, research indicates that asking someone directly about thoughts of suicide does not “give them ideas”

Be sure to ask Manjeet directly,

“Are you having thoughts of suicide?”

By encouraging her to avoid any confrontation with the in-laws in order to stay safe especially since they now knew Manjeet was no longer “in their control”.

According to the National Domestic Violence Hotline, leaving can be the most dangerous time for survivors, as the person causing abuse may feel they are losing control and may react violently.

By taking charge of her birth control.

CDC data from 2018 to 2019 showed that women aged 15-44 faced a 16% higher risk of being killed if they were pregnant or within one year of pregnancy compared to those who were not pregnant for the same age group.

The Sikh Family Center peer counselor and Manjeet’s sister discussed how Manjeet’s mother would call the mother-in-law’s phone, how she would ask her to give the phone to Manjeet, and how she would share coded messages with Manjeet to convey: help was available, she was not alone. They also practiced saying to the in-laws that no one wanted to have an injury or a death on their hand and that it was in no one’s interest that more police be called to the house. In this way, they put the in-laws on notice, while also keeping them pacified!

Then, Manjeet told her sister, in a hushed voice, “Get me out!” This put everything in action.

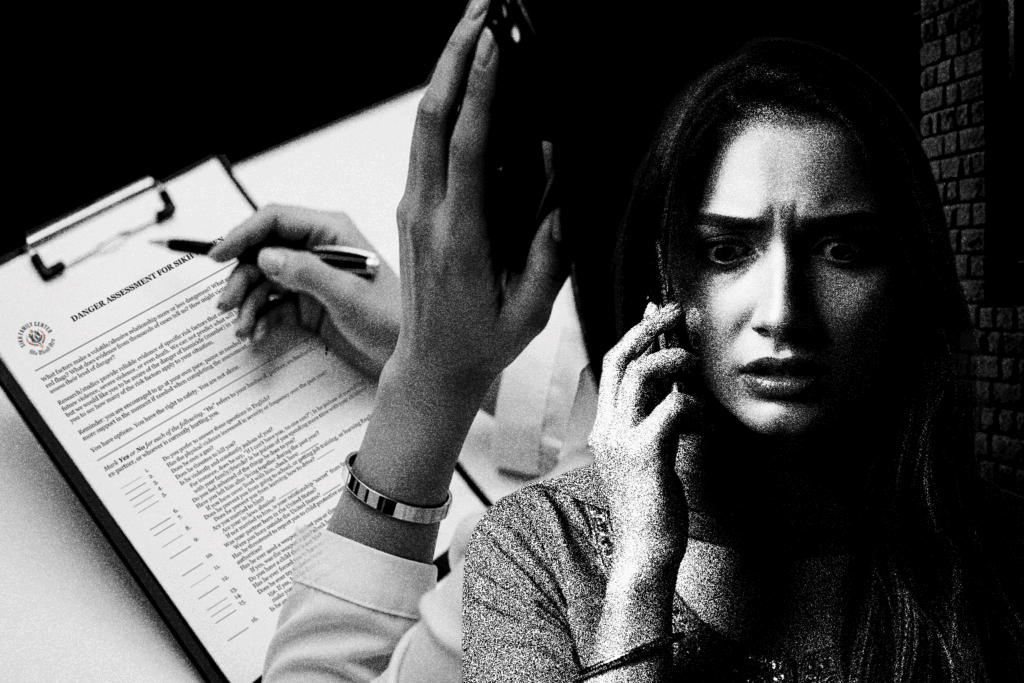

Using the Sikh Danger Assessment tool created by Sikh Family Center, the peer counselor and Manjeet’s family had already discussed how Manjeet was at high risk of lethality. With the family’s permission, Sikh Family Center contacted a local Domestic Violence (DV) resource center, and through them planned to transport Manjeet to the local shelter. Sikh Family Center had advocated for Manjeet’s particular needs, including her language requirements: she was fluent in English, but culturally hesitant to speak it. We had also lined up legal next steps, since Manjeet’s family was worried her in-laws and husband would stalk her and hurt her if she left the house in which she had been held prisoner. The DV agency staff had collaborated with Sikh Family Center staff to plan how best to support Manjeet with her wish to leave the house, without a cell phone to freely call them, or the police.

You can call the police from a phone without a SIM, but if you are doing so please try to find out your location because police cannot easily call back or locate such a phone, while the abusive party might find out that such a call was made, making the situation more dangerous.

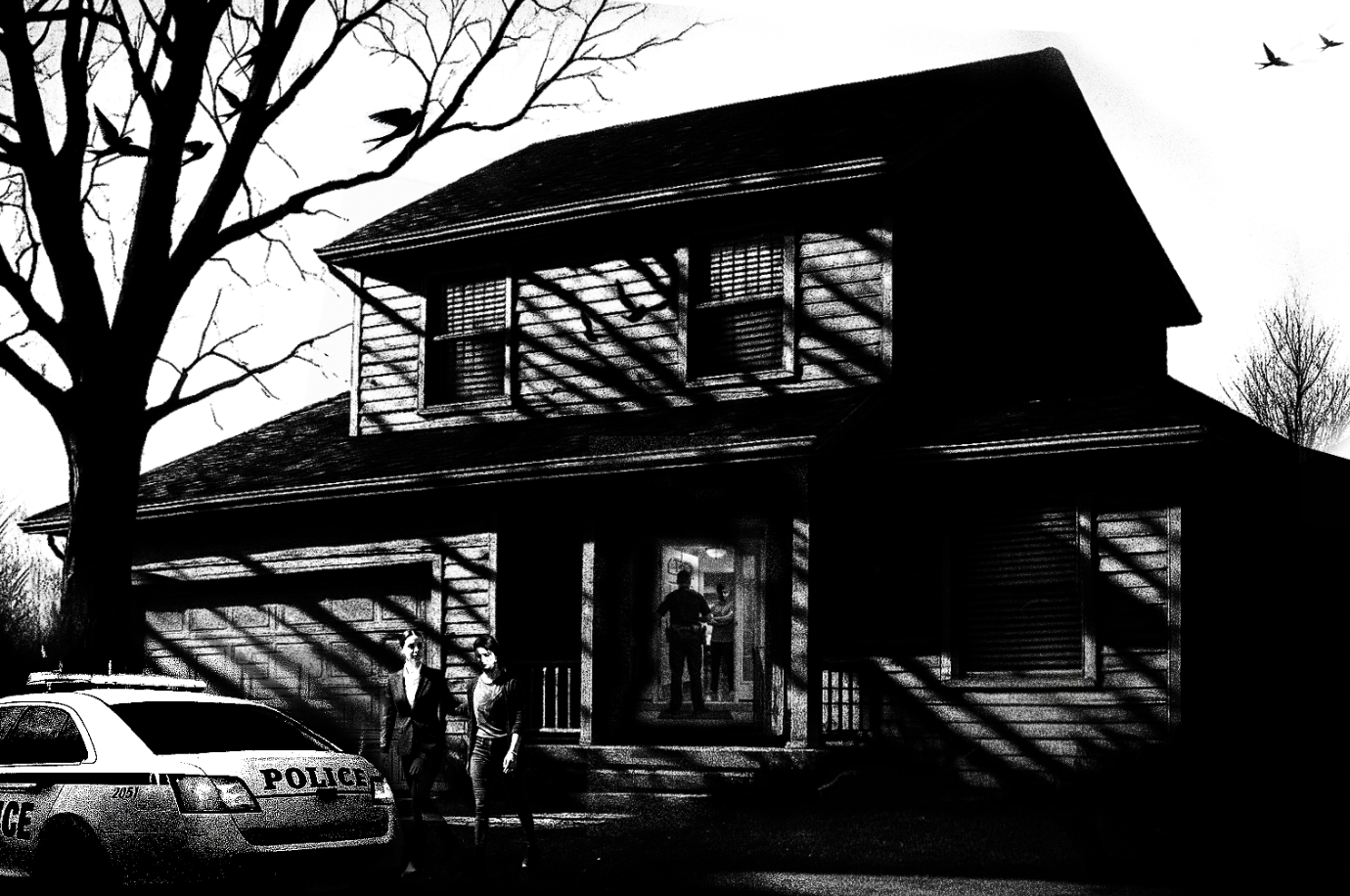

Simrat was to call a police precinct number in the county where Manjeet lived and mention the local DV agency staff had agreed to send their representative to work with the dispatching officer. She also managed to get Manjeet’s exact address from their relatives.

This was a crucial partnership plan: the last time police had responded to the 911 call to conduct a wellness check on Manjeet, Sikh Family Center learned the officer had not spoken with Manjeet alone. Now we had planned for someone from the DV agency to advocate with the police to follow the correct protocols, speak with Manjeet privately, and share some safe resources.

Just in Time!

Simrat called the police precinct number. The planned multi-agency response took place, with our peer counselor coordinating between Simrat, the DV agency, and the police. Manjeet safely left her husband and in-laws’ home with the DV advocate. Manjeet was visibly shaken, had endured a great deal of trauma, but told the DV advocate they had come “just in time.”

Then, as soon as Manjeet got on the phone with Simrat she shared a chilling update no one outside the house had yet known: Days before, her in-laws had purchased a firearm.

Having a gun in the house in domestic violence situations increases a woman’s risk of being killed by 500%. More than half of women fatally shot are killed by family members or intimate partners.

They had then sat Manjeet down at a dining table. They surrounded her and forced her to write an ominous note- ‘Jay minu kuch hogaya, te mai hi zimivaar han’ – ‘If anything happens to me, I am the only one responsible’.

Manjeet said she knew they were planning to use her suicidal thoughts and mental ill-health against her, to get “rid of her.” She said Simrat had acted in the nick of time!

Throughout this ordeal, Manjeet’s resilience and courage shone through. Despite the isolation, her fear, and her ill-health as a result of the trauma, she took the opportunity to reach out to her family, communicate her situation and ask for help.

As per Sikh Family Center’s 2019 survey, Sikhs who identified as survivors of family violence reported experiencing more than double poor mental health days (in the past month) compared to other Sikh respondents.

Manjeet provided consent to the DV agency to talk with her family as well as Sikh Family Center, to share regular updates. With a new phone, she could safely contact her family now. She received medical care. She completed an intake with the agency and stayed at their shelter, which was in an undisclosed location.

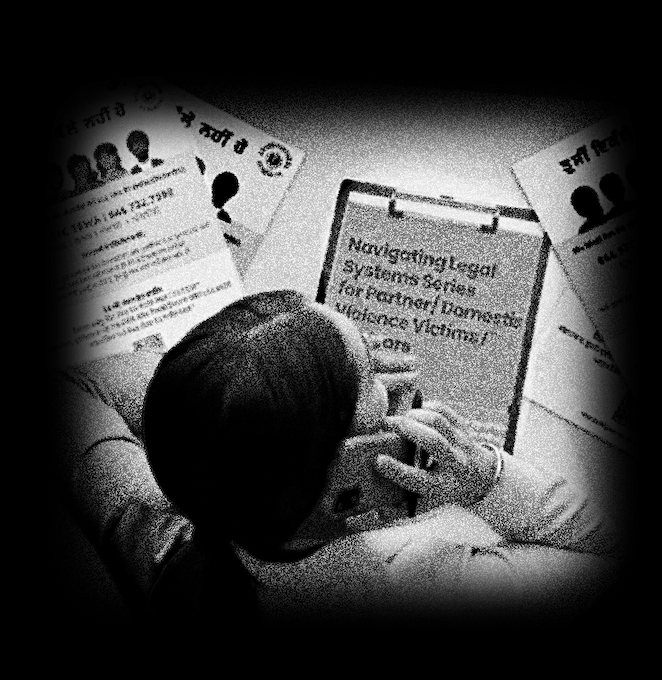

Over the next several months, advocates at the DV agency supported Manjeet through their programs and resources. Sikh Family Center’s peer counselor provided information on the legal options that Manjeet had, how to navigate the legal systems, file for a restraining order, document the abuse starting with the most recent incident. She also had Manjeet think about her future – look for work so she could support herself. Shelters usually house survivors for around 30 days, and so thinking about housing options was imperative.

The path ahead isn’t easy. Manjeet’s in-laws have spread rumors. A community member who became her supposed champion dissuaded her from filing for divorce or starting to work sooner—saying “bechaari, you’ve gone through so much, you need more time to think.” Her sister and family faced opposition from their own circles.

But Simrat remained her steadfast support, keeping her whole family, and Manjeet, in chardi kalaa! This Kaur has inspired not only her own sister but all of us. And her bhenji Manjeet is now on a path of healing, self-discovery and self-determination. Her hope is Aman and her in-laws don’t trap another girl into their web of deceit and damage.

Manjeet’s story is not an exception.

It is the story of one of many Sikh sisters living trapped in fear inside the very place they were taught would be ‘teraa apnaa ghar.’

It reflects what is happening in our sangats, at our Gurdwaras, in our neighborhoods, in our homes.

You are not alone.

If you, or someone you know is experiencing gender-based violence, we encourage you to reach out to Sikh Family Center’s National Non-Emergency Helpline. Our compassionate, culturally responsive, bilingual (Punjabi and English) peer counselors are available to provide private conversations and non-judgmental support, and appropriate resources as you create a safe and healthy future for yourself and your loved ones.

The health of a nation begins in the homes of its people.

**Disclaimer: All names, dates, and identifying details in this story have been changed to protect the privacy and safety of those involved. The images have been created for illustrative storytelling purposes only, consistent with standard practice for narrative visual work.**

- Image credits: Satveer Singh

- @projectaananta